Since some time in the 7th century, parchment/paper has been the dominant method of recording and preserving legal materials such as laws, regulations and court opinions. Today, we are witnessing an accelerating move away from paper towards purely digital methods of producing, recording and preserving legal materials.

The benefits of the move away from paper are many and mostly obvious e.g. cost savings and efficiencies. However there is a problem area that is less obvious but potentially quite serious unless addressed before the complete eradication of paper from the law publication/promulgation process.

Simply put, the combination of paper and ink has an inherent property known as fixity which digital documents lack. Fixity is the property whereby a paper document such as an Act or a Supreme Court Opinion, can be relied upon, perhaps for centuries, to precisely say exactly what it said when the ink was applied to it.

Simply put, the combination of paper and ink has an inherent property known as fixity which digital documents lack. Fixity is the property whereby a paper document such as an Act or a Supreme Court Opinion, can be relied upon, perhaps for centuries, to precisely say exactly what it said when the ink was applied to it.

Fixity is the property that allows, for example, a Secretary of State’s office to hold “master” versions of Laws/Regulations that can be referred to in perpetuity if ever there is a question mark over what the correct text of the law actually says.

Referencing back to paper in this way is a laborious process for sure, but it is one that has stood the test of time for centuries as a surefire guarantee of authenticity. It is a “gold standard” if you will, for recording, preserving and demonstrating the law of the land. Regardless of how many layers of extra convenience are added by copies, compendia, electronic versions, search engines and so on, the originals are always there in the vaults, should the need arise.

We are now approximately five decades into the ongoing computerization of lawmaking processes and publishing of legal materials. For most of that time, paper has continued to play a mostly underappreciated role as the “master version.”

Disclaimers on legislative websites for example, stating that paper versions of legal materials remain the official ones, have been commonplace since the early days of CD-ROMs and now, the internet.

Things are changing now however. Several states have already moved some of their legal materials to an electronic-only environment. In the absence of paper, how is it possible be sure that the legal text you are reading is accurate? What is the “master version” in a world in which all versions have become electronic and lack the fixity of paper?

What is the “master version” in a world in which all versions have become electronic and lack the fixity of paper?

Uniform Electronic Legal Material Act (UELMA)

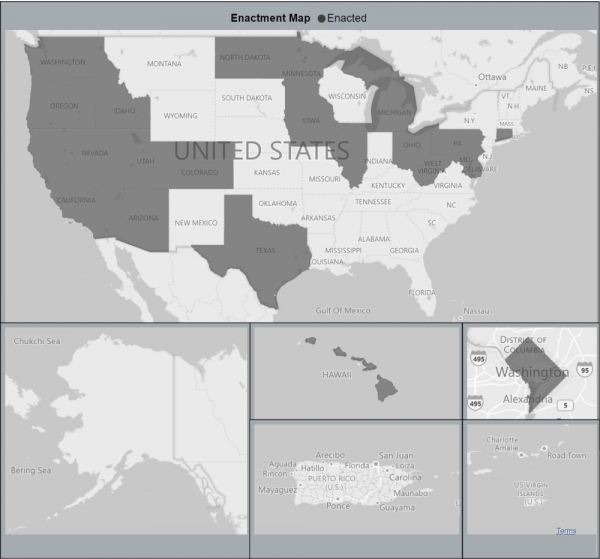

In 2011, the Uniform Law Commission produced a model law addressing this question known as UELMA – the Uniform Electronic Legal Materials Act. Almost a decade has passed since then and to date, twenty states plus the District of Columbia have enacted laws based on UELMA.

Sounds good, right? States are addressing the issue. Well, yes and no. Firstly, we have a long way to go before all 50 states have UELMA-like legislation. Secondly some states are currently operating electronic-only environments with no UELMA-like mechanisms in place.

This is worrying because we do not know what will happen if and when the need to refer to a “master” version of the law arises. In the digital world, all the fixity aspects of paper disappear by default. Digital copies and copies with slight variations are created all the time. Pinning down a single electronic file and saying “this is the real one” is well nigh impossible unless technical steps are taken to create it. In the interests of continuity, this should be done before the final paper “master” disappears.

Some states that have taken steps in the direction of UELMA implementation have partial solutions at present. For example a state may have a solution in place for executive branch materials such as Registers and Administrative Code, but may not have a solution for legislative branch materials such as Session Laws and Journals.

Variations can be seen in what document types different states choose to focus on. For example, in some states the journal is the official record of all new legislation and thus is arguably a better “master” than the Acts themselves. In some states, codified statutes are prima facia sources and in principle, can be recreated from the Session Laws which may be considered “master.

PDF+PKI and Hash+HTTPS

UELMA is purposely non-descriptive about how states should authenticate, preserve and enable long-term access to legal materials. This makes sense as there are many different technical approaches to UELMA that can be taken. It is striking that the implementations over the past decade have coalesced around two quite different approaches. I call them the PDF+PKI approach and the Hash+HTTPS approach.

PDF+PKI

The PDF+PKI approach uses PDF versions of legal materials that are authenticated with “authentication ribbons” that appear in PDF readers such as Adobe Acrobat. The authentication ribbon is driven behind the scenes by Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) for digitally signing and attesting the source of the PDF. This is the approach used in the Federal Government and California for example.

Hash+HTTPS

It is striking that the implementations over the past decade have coalesced around two quite different approaches. I call them the PDF+PKI approach and the Hash+HTTPS approach.

There are pros and cons to both of these approaches. For the PDF+PKI approach, the main pro is that it facilitates a seamless user experience for the consumer of the legal material in the case of PDFs. Not only can the accuracy of the material be relied upon but you can also be assured of who produced it.

The main con is that the seamless user experience really only applies to single PDFs. A second issue is that the use of PKI carries with it extra implementation costs and an ongoing cost related to cryptographic key management.

The Hash+HTTPS approach works with any type of file (and indeed bundles of files, including PDFs). It is technically simpler to deploy and maintain. On the flip side, the user experience is not as seamless as it is with the PDF reader’s “authentication ribbon.” It is also, theoretically, more open to what are known in cryptography as “man in the middle attacks.”

So which one is best?

- Step 1: I go to the publishers website. In this case https://www.videolan.org/. It has the HTTPS padlock icon which tells me that my link to that website is secure.

- Step 2: I find the download link on that website along with the checksum number (another word for “Hash”).

- Step 3: Having downloaded the file, I can run a utility program to calculate the checksum for my downloaded file. If my checksum and the checksum on the original website match I can have a high degree of confidence that my file is exactly the file “as published”.

Exactly the same approach is being used daily by internet users downloading operating systems, documents, video files, zip files, spreadsheets, you name it. This is also the approach used in Europe for EU legislation in the CheckLex system (https://checklex.publications.europa.eu) with the added feature of an online service that allows you to upload a file and check its authenticity online.

As with all things security-related, there are no perfect answers. The market, professional communities of practice, and indeed complete societies will always seek to balance maximum security on one hand with pragmatic ease of use on the other.

The internet as a whole has overwhelmingly voted for Hash+HTTPS as a pragmatic way of handling the authentication issue and I expect this approach to be the one that gets widespread adoption in lawmaking environments. I also expect that we will soon see this approach baked into the browsers we use on a daily basis so that downloads are automatically compared against their checksums.

The internet as a whole has overwhelmingly voted for Hash+HTTPS as a pragmatic way of handling the authentication issue and I expect this approach to be the one that gets widespread adoption in lawmaking environments.

Looking beyond the authentication of legal materials at a point-in-time, the next obvious desirable feature is the ability to establish the provenance of legal materials in an all-digital world. In other words, having a mechanism of checking the version history of a legal document – or even better, an entire corpus of legal documents – would actually move us past trying to be at least as good as paper was in the past.

It would move us to something that is far superior to what paper ever was or ever could be. I.e. a moment-by-moment, edit-by-edit digital history of the laws of the land. All made available by publishers to allow a level of auditability, transparency and permanence that paper could never provide.

In LWB 360 we are fortunate to have a foundation that has always been based on this edit-by-edit level of deep auditability. We support both the PDF+PKI and Hash+HTTPS approaches but we are recommending the latter to our clients implementing UELMA as we believe it is the approach that will dominate UELMA implementations in the years ahead.